Blog and news

Species Spotlight: Chatham Island mudfish

Scaleless and silky-smooth, the elusive Chatham Island mudfish lives in the dark peat-stained depths of Rēkohu/Wharekauri’s lakes. In this month’s Species Spotlight, mudfish researcher Grace Fortune-Kelly shares some of her favourite mudfish facts.

Mudfish are experts at wetland life.

Mudfish, or Neochanna, are a genus of six Australasian species – five across Aotearoa (including Rēkohu/Wharekauri) and one in Tasmania. They diverged from the rest of the galaxiid family to be wetland specialists with almost eel-like body shapes. To survive in wetlands, they’ve evolved to tolerate harsh conditions, including low oxygen and high acidity (sometimes the acidity of wetlands is comparable to orange juice).

They’re often found in small remnants of water at the base of fallen trees, for example, or in small patches of low-flowing water in streams. They're commonly found as the only fish species in their habitat, leading to speculation they may not be great with competition if other fish appear on the scene.

The Chatham version specialises in lakes.

Unlike the other mudfish species, Chatham Island mudfish - Neochanna rekohua - live in lakes. This may relate to the vacant niche that's arisen from a lack of other inland freshwater fish species. They do survive alongside tuna (longfin and shortfin eels, Anguilla spp.) and, in one lake, alongside common smelt (Retropinna retropinna).

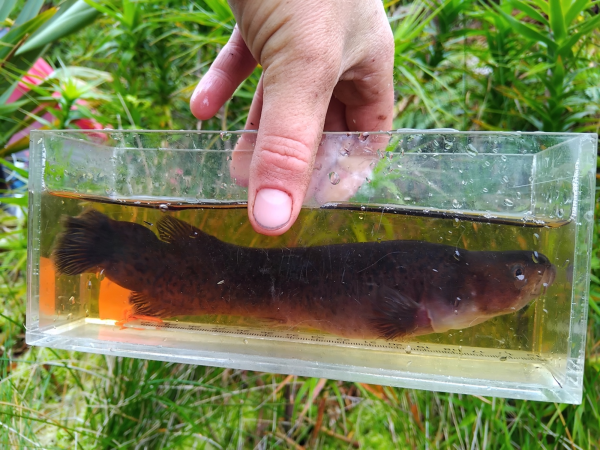

Large mudfish from Lake Rakeinui. Don't pick up mudfish at home! Image: Grace Fortune-Kelly

No one’s sure how they got where they are...

How exactly the mudfish colonised Rēkohu remains a mystery. Their distribution across the island adds to the enigma.

Mudfish were first recorded in 1995 in just two lakes in the southern tablelands, where dracophyllum forest is intact and wetland remains. However, another population was reported in 2019, in a lake on the opposite side of the island. And yet, there are at least 10 other lakes between these ones that have no sign of the fish.

They do have a diadromous (which means they move between salt and fresh water) ancestor, which is likely how these fish would have ended up in different areas - but did they colonise just these lakes on multiple occasions? Were they once in all the lakes, but got wiped out? Are there some environmental variables filtering where they're distributed over the island? I'm hoping to find out more about this as part of my research and learn about the kind of conditions and habitat Chatham mudfish thrive in, so that conservation efforts can be targeted and effective.

Map showing the discovery of Chatham Island mudfish populations. Image: Grace Fortune-Kelly

Their diet is also a bit mysterious.

Dark, peat-stained waters, like where these mudfish live, don’t let in a lot of light. This means plants (including microscopic phytoplankton) can’t thrive, and the water has low productivity. So what do these mudfish eat?

There hasn't been an abundance of invertebrates found in these lakes, but mudfish do seem to find enough insect (especially fly) larvae and microcrustaceans for sustenance. One of these is a tiny microcrustacean called bosmina, also known as the “elephant water flea”. Despite the huge name, they’re less than one millimetre long. Terrestrial adult flies, beetles and cicadas make it into mudfish diets, and they’ve also been caught eating each other. Guess you can’t be too fussy when options are limited.

Mudfish surveying headquarters. Image: Grace Fortune-Kelly

They max out size at just over 20cm - huge for a mudfish!

In lakes where tuna and mudfish co-occur, Chatham Island mudfish average around 50mm and grow up to about 100mm. Without tuna though, they grow to more than twice the size, to over 200mm! The biggest fish on record is a 211mm individual from Lake Rakeinui.

Since their fins, head and body shapes change dramatically as they grow, these larger fish almost seem like a different fish all together. The images below provide a great example – both show the same container holding fish from different locations. First, some of the bigger fish from Te Rangatapu, a lake that has tuna; second, a single record-breaking fish from Rakeinui, a mudfish-only lake. They look very different!

Small adult mudfish from Te Rangatapu, Image: Grace Fortune-Kelly

A record-breaking adult mudfish from Rakeinui, a lake with no eels. Image: Grace Fortune-Kelly

A personal note from Grace

With some mysterious characteristics, a uniqueness from their other mudfish relatives, and little known about their ecology, I feel lucky to be researching Neochanna rekohua. I started doing freshwater research in on Rēkohu in 2021, and loved it so much that I expanded my project to a PhD at the University of Otago, which I’m now two-thirds of the way through.

I’m hugely grateful to all the landowners who have let me explore your backyards looking for these little fish, and for all the local support. A special thanks to Hokotehi Moriori Trust for hosting us at Kōpinga marae, Tom Lanauze for giving his invaluable insight, Abe Neilson for all the rides, and Hamish Chisholm for being an amazing guide - I would have been lost without you!

Lake Te Rangtapu - mudfish habitat. Image: Grace Fortune-Kelly