Species and environment

Seabird-driven ecosystem in the Chathams

Seabirds are at the heart of the Chatham Islands and the healthy functioning of its ecosystems – and a healthy island means healthy oceans.

The waters of the Chatham Rise are fed by the clashing of the Pacific and Southern oceans, making it the most productive marine area in New Zealand waters. This fertility makes these important waters for seabirds: it’s been estimated that 20% of the world’s seabirds use the Chatham Rise, for breeding, foraging, or migrations.

The coasts and forests of the Chatham Islands archipelago were once teeming with seabird life, from burrowing petrels, to little penguins, to large albatrosses nesting on steep coasts. Even today, the 28 seabird species that breed in the Chathams make it one of the world’s most diverse seabird breeding sites. The islands are also the breeding ground for 99% of the world’s population of northern Buller’s albatrosses and Northern royal albatrosses.

The environment of the Chatham Islands has evolved with a seabird-driven ecosystem.

How a seabird-driven ecosystem works

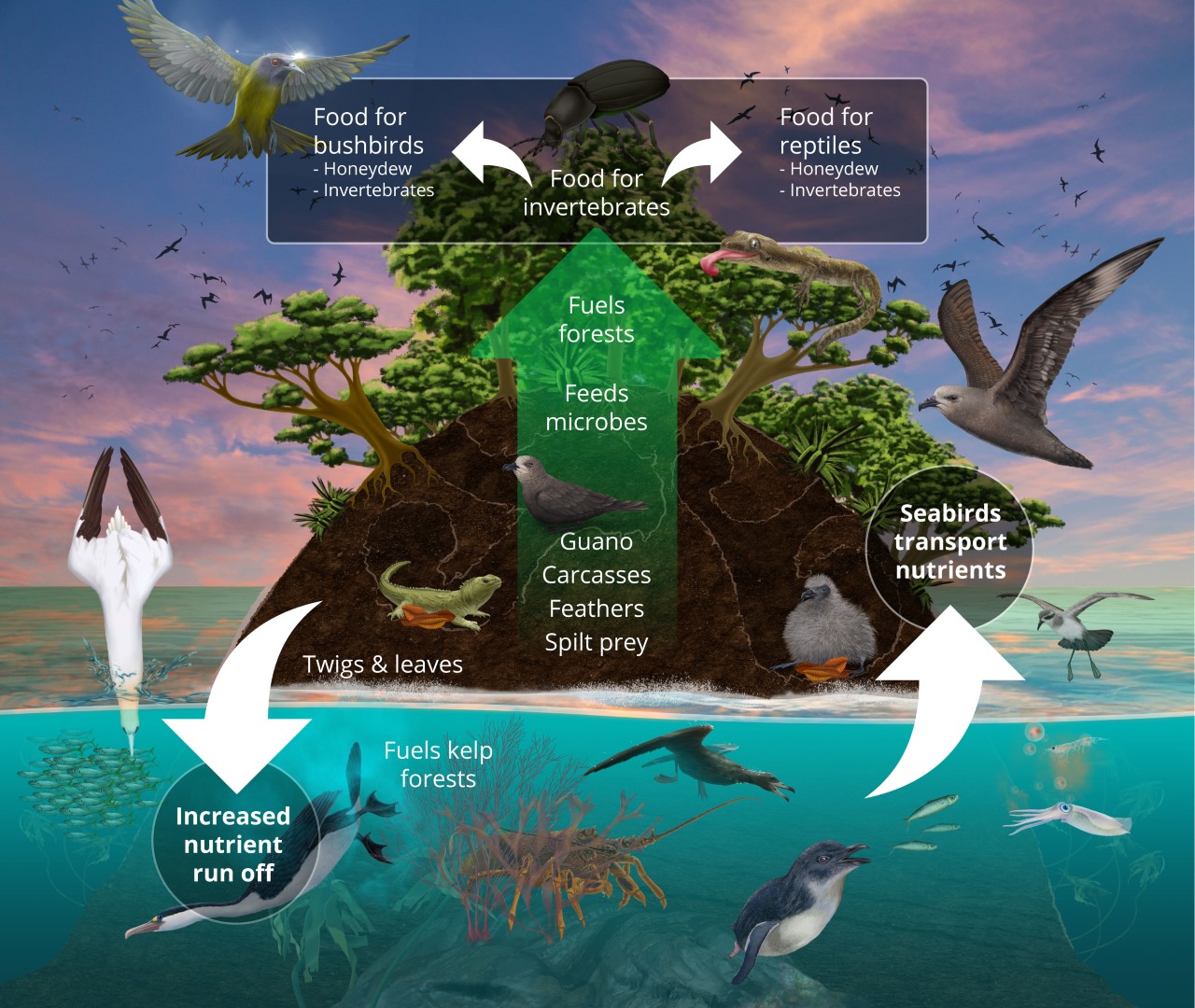

Seabirds are a connector between islands and ocean. They play a crucial role in the land-sea nutrient cycle.

A nutrient cycle is the movement of nutrients from the physical environment into living organisms, then back into the environment and into production. Essentially, it’s nature’s recycling system. In a balanced ecosystem, all species have evolved so this nutrient cycle works effectively.

How a seabird-based ecosystem works (c. Shaun Lee)

On land, there is a natural degree of nutrient loss into the ocean – for example, in run off from rain or weather events. Seabirds are key to bringing nutrients back. On islands, a high percentage of the land is coastal and this role is even more essential.

While out at ocean, seabirds eat fish and marine invertebrates, storing the nutrients in their bodies. When they return to land, they deposit these nutrients, mainly in the form of nutrient-rich poop (guano), but also in spilled fish, eggshells, and eventually their bodies when they die and decompose. Burrowing seabirds take this one step further by delivering nutrients right down into their tunnels in the soil.

All this enriches the soil and has a flow on effect for the rest of the island. It supports the growth of vegetation, helping provide food for other animals like invertebrates, lizards and forest birds. It’s an essential part of the food web.

One of the indicators of a healthy environment is an abundance of insects, and the Chathams have especially diverse invertebrate life. The presence of wētā, speargrass weevil, and stag beetles all suggest a healthy ecosystem.

Seabirds do a bit more to connect sea and land

Seabirds aren’t the only species that are part of the vital island-ocean connection. Shorebirds like shags, and marine mammals like seals and sealions, also bring ocean nutrients to the land.

However, many seabirds travel much further afield, some staying out at sea foraging for 2-10 days. Some of the petrels do a round trip of around 500km, while albatross will do around 700km. Shorebirds and marine mammals stay closer to land. This limits the reach of their nutrient-gathering. When they come ashore, these species also tend to remain near the coastal edges or where they haul up.

Burrowing seabirds not only take nutrients below the ground, but go further inland. The Chatham Island tāiko breeds in very dense bush kilometres back from the coast, bringing nutrients directly into the forest. Other species help with this process – for example, wētā pull a large amount of material underground.

Seabirds also play a crucial part in the marine food web. Their foraging helps regulate fish populations, which prevents overpopulation of certain species and helps maintain the balance of the food web. In turn, this impacts the abundance and distribution of other marine species.

In terms of the volume of nutrients delivered today, the seabirds on the Chatham Leader Board are prions, storm petrels and tītī/sooty shearwaters. On the albatross islands like Motuhara/the Forty Fours, those species are doing the same thing.

A white faced storm petrel on Rangatira/Hokorereoro. Image: Dave Boyle

Protecting seabirds to protect our islands

Thousands of years ago, the coastlines, rocky outcrops and forests of the Chathams were jam-packed with seabirds. Today, loss of habitat and predation by introduced predators have severely impacted many species. For example, there are only 50 known breeding pairs of Chatham Island tāiko and 250 known pairs of Chatham Island petrels.

Seabirds’ role as ‘ecological connectors’, and the impacts introduced predator species can have on them, has been well-documented. Seabirds are particularly vulnerable to rats and feral cats while in their burrows or nests. Even albatrosses, a relatively large bird, can fall prey to feral cats.

Removing predators is a key step in helping seabird colonies reestablish, as well as allowing other animal and plant species to recover. However, the removal of predators (like rats, as this research shows) alone is often not enough for an ecosystem to restore itself. Translocations are one of the main methods used to help reestablish seabird colonies, often supported by human-made burrows or nests and the use of sound systems playing bird calls. Restoration planting and weed control also help healthy habitat reestablish.

Northern Royal albatrosses and button daisy, the Forty-Fours. Image: Levi Lanauze

Ways you can help

Restoring and protecting seabirds means protecting the health and resilience of the islands, and the wellbeing of future generations who live here.

Some simple ways you can help are:

-

Keep clear of seabird nesting spots during the breeding season. Keep dogs under control and cats inside at night.

-

Get involved in local trapping and coastal restoration projects.

-

If you’re fishing, use weighted lines, barbless hooks, and artificial lures. If you’re at sea, steer your boat around feeding flocks.

-

Dispose of your rubbish responsibly so it doesn’t end up at sea. Plastics cause major problems for seabirds and other sea creatures.

- Support conservation in the Chatham Islands.